6 priorities for future research on COVID-19 and its effects on early learning

[ad_1]

As of March 2020, researchers have produced more than 300 reports on the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on early learning and the early childhood education and care (ECE) programs that serve them. Very quickly, CEE leaders faced with the urgent day-to-day demands of the COVID-19 response were also faced with a deluge of evidence, much more than they could effectively find, sort and use.

To help provide decision makers with a clear understanding of the effects of the pandemic on early learning and ECE programs, our team of 16 early childhood experts and 10 early childhood policy makers recently published a summary of this evidence base. We reviewed 76 high-quality studies in depth, covering 16 national studies, 45 studies in 31 states, and 15 local studies. Our work has shed light on a national history of learning setbacks and unmet needs, for which we have proposed evidence-based, equity-focused policy solutions.

But another benefit of taking stock of what we know was finding out what we do not know. Our in-depth review revealed six takeaways about the next steps in research in this area. Especially given that US bailout fund can be used to build research capacity in state and local agencies, we hope that a clear statement of what stakeholders need to know next will be useful in generating new evidence to guide investments in the future.

Here are six priorities for future research:

- Continue to monitor recovery for children, families, teachers and programs. We have probably just scratched the surface of the effects of this fluid and complex crisis. the Delta variant raises new questions about health and safety, and young children have not vaccinated yet. Scaling up studies on the effects of the crisis on children’s learning, the offer of ECE programs and the experiences of early childhood educators is essential to target supports and ensure equitable solutions.

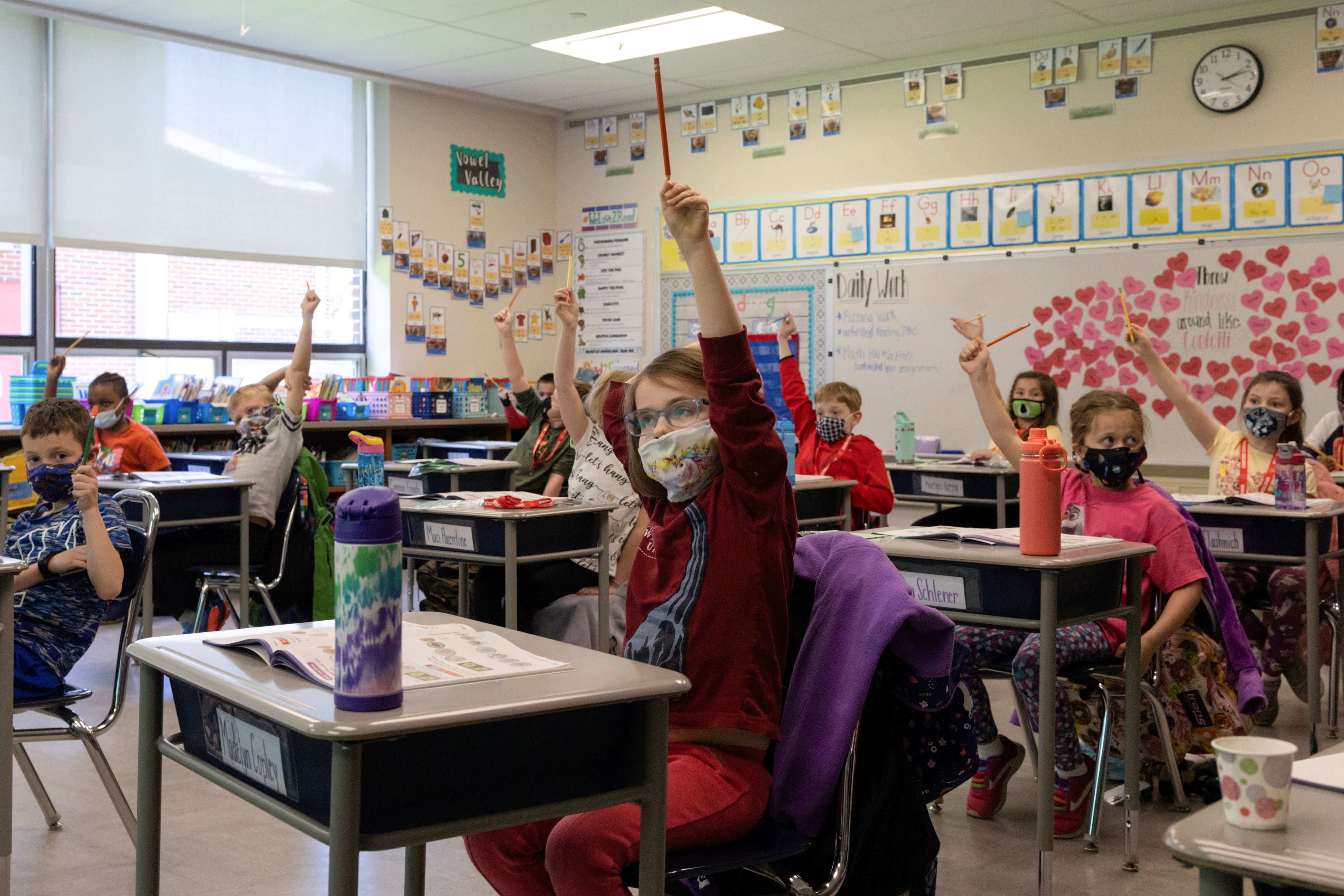

- Document changes to ECE programs and children’s experiences that are not captured in existing data. We have a lot of evidence that shows the many changes ECE programs make to improve health and safety, but we only have crass reports from teachers on the effects of these changes on children’s classroom experiences. . As immunization rates increase, a return to direct observations of ECE classrooms — typically done at large scale before the crisis, should be used to support both children and teachers. How do young children spend their time? Has the quality of teaching declined as indicated by teacher reports? In what areas do teachers need support? Largely used and more recent metrics can answer these questions and inform educational and policy decisions in the new normal.

- Measure learning outcomes for younger learners directly and across multiple subject areas. We found no data from direct assessments of children’s pre-Kindergarten skills, and very little data outside of the K-2 literacy domain. We have reports from parents and teachers of younger children that paint a disturbing picture, but the psychometrics of these measures can be questionable. The direct K-2 assessments we have show consistent and significant learning setbacks, especially for children generally marginalized in the American education system. And many children, especially children from low-income households and children of color, are missing from recent data. Direct assessments are essential for meeting young children where they are, effectively targeting resources and guiding investment decisions.

- Collect systematic data on the ECE workforce. Numerous studies have detailed how the ECE workforce has suffered from the crisis as the pandemic escalates long standing problems such as very low pay, limited benefits and little professional support, especially among teachers in home and child care. Faced with new challenges, early educators also reported new professional development needs, including training in health and safety, distance learning, and meeting the needs of bilingual learners (DLLs). Unlike Kindergarten to Grade 12, where a lot of data is collected on teaching staff, few states systematically collect data on the first educators. Collecting this data from all sectors will be essential as new investments are made. ECE workforce issues typically undermine investment, and early childhood educators are central to ensuring high-quality experiences that help young children thrive.

- Prioritize research on hardest hit groups. We know that the effects of the pandemic have not been supported in equal parts, but we found no data on some key populations such as young children from homeless families, bereaved children, children from migrant families, and Asian American children amid the rise of Asian-American hatred. Data on other critical populations such as DLLs, children with disabilities, and Native American children are scarce. Equity-centered and evidence-informed decision-making requires more data on young children who belong to groups that have suffered the most from the crisis.

- Evaluate the impacts of new investments. We will need more rigorous and fast research as states and communities make high-stakes political and spending decisions and families make decisions about the care and education of their children in the next chapter of the crisis. Decisions on a diverse set of topics (for example, program eligibility, teacher compensation and professional supports, and interventions for students in need of assistance) provide both unique opportunities to study bold policies and have the potential to have lasting impacts. For example, Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, a state particularly affected by the crisis, recently announced historic investments in the two childcare and preschool, including expanding access and improving teacher remuneration. Maine and Washington state also announced significant new investments. It is essential to document state and local political choices and their impacts. This will help legislators make decisions on how best to allocate the recovery dollars and ensure that what we learn from these historic investments will guide long-term efforts to create truly high-quality EPE systems.

We titled our abstract: “Historic crisis, historic opportunity.” March 2021 American rescue plan was the largest public investment in early childhood care and education in U.S. history. Smart and rigorous research, especially in partnership with policymakers, has a critical role to play in moving from crisis to opportunity in ECE. Our young children and our early childhood educators deserve no less.

[ad_2]